During the late-1950s the aircraft manufacturer Saunders-Roe built and tested the first practical hovercraft, the SR-N1, thereby validating designer and inventor Christopher Cockerel’s theories that it was feasible to manufacture fast craft capable of operating over both land and water.

Other UK companies including Vickers-Armstrong and the shipbuilder William Denny & Co quickly joined the race to develop and manufacture commercially viable hovercraft.

The hovercraft is unique. It is designed to travel over a surface supported by a cushion of high-pressure air, though it can also float like a boat if required.

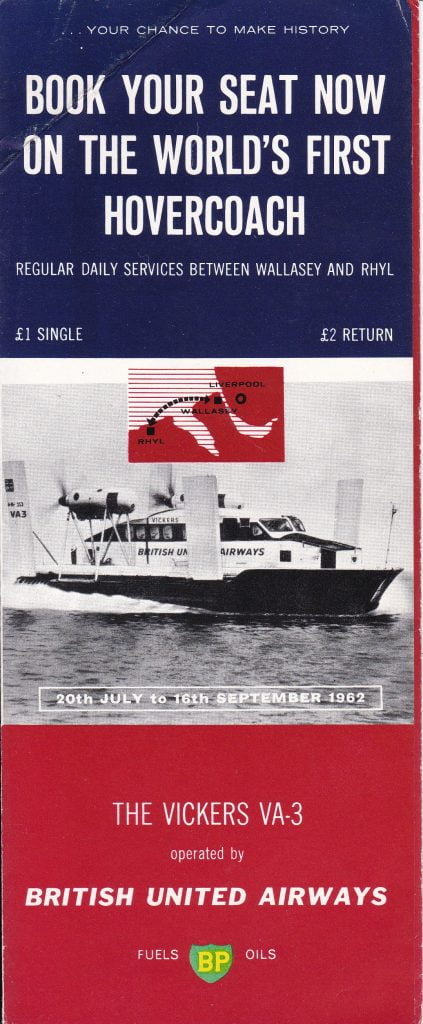

In July 1962, the Wirral became the unlikely location for the world’s first passenger and mail carrying hovercraft service. Owned by British United Airways and managed by Furness Withy Ship Management Ltd, the Vickers-Armstrong hovercraft VA3-001, weighed ten tons, and was designed to carry 24 passengers and mail at speeds up to 60knots (69mph, 111kmh).

However, as VA3-001 was designed without a skirt. Hovering just eight inches above a solid surface, the lack of skirt restricted its use to spells of calm weather.

The service, of six return trips a day between Leasowe embankment and Rhyl, commenced

on 20 July and was scheduled to operate for two months for experimental purposes. Hoylake had been first choice for the Wirral end of the operation, but Leasowe was decided upon as it

had a flat beach and would reduce engine noise. Though the service proved extremely popular, a combination of engine failures and weather conditions resulted in it operating for only 36 days. Fares were, single £1, return £2 (£17.75 and £35.50 respectively at August

2023 prices).

On Friday 14 September 1962, the day’s service was cut short due to failure of one of the hovercraft’s lift engines. Bad weather prevented engineers from carrying out repairs, and the

following Sunday, VA3-001 broke free from its moorings and drifted out to sea. Her duty pilot, Captain Old, who had remained aboard, managed to fire up the propulsion engines and when the tide receded brought the hovercraft onto the beach. Unfortunately, VA3-001 broke free again the following day and had to be rescued by the Rhyl lifeboat. Having suffered structural damage, the hovercraft was withdrawn from service.

The following year Denny Hovercraft, a subsidiary of shipbuilders William Denny & Co, Dumbarton, commenced a service on the Thames using hovercraft D2-002. Originally designed for the Royal Navy, D2-002 could carry 70 passengers at speeds of up to 25knots (28.7mph, 46.3kmh).

Having tested a prototype on Gareloch in June 1961, Denny commenced construction of their D2 design, a sidewall type lacking the inflatable skirt that most of us would instantly recognise. When D2-002 was ready for sea trials, it is said that her Captain/Pilot Cyril Perrigrin had first to obtain permission from the Harbour Master to manoeuvre out of the yard and into the Clyde and then seek permission from Air Traffic Control, Renfrew Airport to engage the engines for lift off. When the Interservice Hovercraft Trials Unit rejected D2-002, it was sent on an epic 820-

mile trip to the Thames where it was employed as a ‘hoverbus’ between Westminster and the Tower. It was not a success due to damage sustained from floating debris and driftwood. During 1963, the Bristol-based ferry company P & A Campbell operated a SR-N2 hovercraft service between Weston-super-Mare and Penarth. Developed by Westland and Saunders-Roe and first flown in 1961, this Bristol Siddeley Nimbus-powered 27-ton hovercraft could carry 48 passengers.

Following modifications to the skirt, it later operated between Eastney on the Solent and Ryde on the Isle of White. In 1965 Hover Travel commenced a full hovercraft service between the Isle of White and Southsea. It is still going strong nearly sixty years later. The Solent is ideal for hovercraft operations as not only are they far quicker than other ferries, they also have the advantage at low tide of being able to disembark passengers in Ryde rather than at the end of the pier.

The Solent was also the scene of the first fatal accident involving a hovercraft in the UK. On 4 March 1972, Hover Travel SRN6-012 with 27 people on board was crossing to Southsea in heavy weather. The 38-50knot (43.7mph-57.5mph, 70.3kmh-92.54kmh) wind as well as wave conditions forced the pilot, Captain Anthony Course, to reduce to half-speed (25knots, 28.7mph, 46.3kmh).

About 400 yards off Southsea, the hovercraft dug into a wave. It was hit by another causing it to list heavily to port. The passengers were scrambling out of the hovercraft when it capsized and one of them, sub-lieutenant Andy Benford (21) RN was thrown back inside the cabin area. He soon found himself in an air-pocket with water up to his knees. Thankfully, he could make out where an open window was located, took a deep breath, and swam for it, coming to the surface where his brother, flight-lieutenant Tim Benford (27) RAF, was sitting on the upturned hull.

As the incident was close to Portsmouth naval base, rescue vessels and helicopters were soon on their way, though first to arrive was the Trinity House Pilot Vessel Vigia, which took sixteen survivors Portsmouth then returned to the stricken craft, remaining on station until the search was abandoned that night.

The hovercraft sank but was recovered later, dragged the final yards to shore by the muscle power of people pulling on a rope.

In all 22 people were rescued, the last to leave being Captain Course. Four bodies, including that of the youngest victim seven-year-old Julie O’Connell were also recovered. However, 48-year-old David Jones was never found and was presumed drowned. Up to the tragedy

Hover Travel had made 110,000 crossings and carried 2.25million passengers without a major mishap.

The official inquiry concluded that the loss of SRN6-012 was due to an “unusual combination of circumstances.” No blame was attached to Captain Course, Hover Travel, or the hovercraft’s manufacturer.

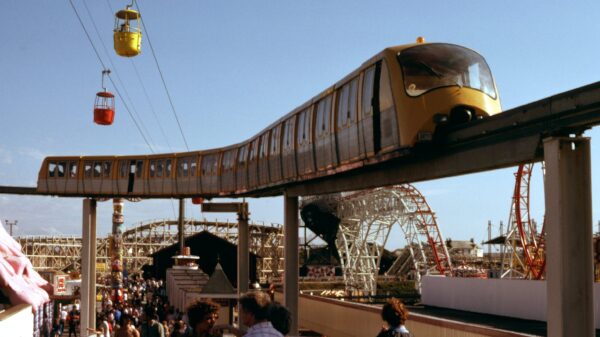

On 1 March 1966, Saunders-Roe merged with Vickers-Armstrong to form the British

Hovercraft Corporation (BHC) and in October 1967 they rolled out the first of their SR-N4 Mountbatten class hovercraft at Cowes on the Isle of White for the benefit of the press. At 130ft (39.6m) long, with a beam of 78 ft (23.7m) and weighing 165 tons, SRN4-001 was designed to carry 254 passengers and 30 cars at a service speed of 65knots (74.8mph 120.4kmh).

The following month SRN4-001 was fitted with her cushion (skirt) and commenced sea trials on 4 February 1968. Powered by four Rolls-Royce Proteus engines, she was robust enough to operate in Force 8 gales and sea swells up to 11.5ft (3.5m).

During August 1968, a new chapter in the history of crossing the English Channel opened when the Mountbatten class SR-N4 Princess Margaret GH-2006, inaugurated the Seaspeed service between Dover and Boulogne. Princess Margaret later operated on a service between Ramsgate (Pegwell Bay) and Calais.

Though the SR-N4s were successful, their Achilles heel was their limited vehicle carrying capacity compared to that of the large ferries coming into service. On 1 October 2000, the Princess Margaret made her final channel crossing and the SR-N4s were consigned to history. Elsewhere, hovercraft attracted interest from the military including the Royal Navy and the Royal Marines.

Founded in 1966 the Hover Club of Great Britain promoted the recreational use of light hovercraft, and it is still going strong to this day.

In the 2020s light hovercraft are operated by some of our Fire & Rescue services as well as by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.